I reproduce the following from the blog site of the Ronald Knox Society of North America (hence the American English spelling). It is worth ten minutes of anybody's time.

The Holy Spirit

If a man should set out to go through the Bible, pausing and making a meditation wherever he found

material, his attention would be caught without fail, I think, by the second verse of it. “Earth was still an

empty waste, and darkness hung over the deep; but already, over its waters, stirred the breath of God.”

Creation still in the melting-pot, so that we have nothing for our composition of place except a formless

sea of undifferentiated matter; dark, not by some effect of shadow, but with that primal darkness that

reigned before light was made. And over this inert mass, like the mist that steals up from a pool at

evening, God’s breath his Spirit, was at work. Already it was his plan to educe from this chaos the

cosmos he had resolved to make, passing up through its gradual stages till it culminated in the creation of

Man.

Deep in your nature and mine lies just such a chaos of undifferentiated matter, of undeveloped

possibilities. Psychology calls it the unconscious. It is a great lumber-room, stocked from our past history.

Habits and propensities are there, for good and evil; memories, some easily recaptured, some tucked away

in the background; unreasoning fears and antipathies; illogical associations, which link this past

experience with that; primitive impulses, which shun the light, and seek to disguise themselves by a

smoke-screen of reasoning; inherited aptitudes, sometimes quite unexpected. Out of this welter of

conditions and tendencies the life of action is built up, yours and mine. And still, as at the dawn of

creation, the Holy Spirit moves over those troubled waters, waiting to educe from them, with the

cooperation of our wills, the entire life of the Christian.

The moment you begin to speculate why you started humming such and such a tune at such and such a

moment, or why you dreamt last night of a friend, long dead, who in your dream was alive, you catch

some glimpse of the vast network of association there must be below the level of consciousness. Have

you ever tried to eradicate sorrel from a garden path? Or even thistles? Those long ligaments which

connect one patch of weeds with the next make a good image of what mental association must be like, if

it could be unearthed to our view. Nowadays, there is so much novel-writing and so much art criticism

which exploits the findings of the psychoanalysts that we are, if it is not too paradoxical to put it in that

way, perpetually unconscious-conscious. We are forever turning in upon ourselves, and scrutinizing the

hidden sources of our own conduct.

What I want to suggest, in giving you a meditation about the action of the Holy Spirit on our lives, is that

there is a further, rather interesting parallel between the chaos out of which the world was formed and the

chaos with underlies consciousness. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the discoveries of

the scientists, and of Newton in particular, had dominated men’s minds with the notion of order and

mechanical sequence in the world of nature around us, the thought of the day became infected with the

tendency which we remember under the name of Deism. Philosophers who believed, sincerely enough,

that the existence of the universe could only be attributed to a creator, restricted his role to that of a

creator and let it stop there. He had made (these people told us) a piece of mechanism so flawless in its

construction that it could roll on its course by means of some self-regulating principle without any further

interference. How they managed to remain satisfied with such a naïf doctrine, it is difficult to see. Nobody

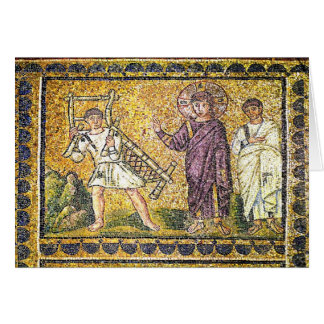

who contemplates Michael Angelo’s picture of the creation of Adam can fail to be impressed by the

gesture of the outstretched arm, which seems to suggest that Adam is just letting go; how far, we wonder,

and in what sense was it possible to let go? But I am not concerned to discuss the difficulties of the

theory, held by people who were Christians after a fashion, which left no room for the divine

conservation, left no room for miracles or the intrusion of the supernatural; which regarded the whole of

creation as a mere fait accompli, set in a mould.

And, if you come to think about it, that is exactly the danger which the new psychology has for you and

me. It tends to make us think of ourselves as set in a mould, certain to react in this or that fashion to this

or that stimulus, because that is the way we are built. Or rather, that is the way we have got warped, by

the impressions we get in extreme youth, long before we’ve attained the use of reason. The first seven

years of our lives are like the seven days of creation, the only really formative period; after that, nothing

will make any difference – except perhaps going to a psychoanalyst. Oh, we go on fighting against our

temptations, but with the feeling that the dice are loaded against us; we are obeying the call of something

so deep down in us that we can’t get at it – that is the frame of mind we find ourselves in, when we have

been coming across this modern talk about psychology.

If you want to get a complete reversal of the eighteenth-century Deist approach, you have to go back to

the Middle Ages. How splendidly the medieval people took everything in their stride! To them, the

constant stir and motion in the world around them was the work of the Holy Spirit – the rustling, as it

were, of his passage; that “the spirit of the Lord fills the whole world” was as clear to them as to the

author of the Book of Wisdom. So it was that Adam of St. Victor wrote, in his hymn Qui procedis ab

utroque:

“Love, that equally enchainest

Son and Father, Love that reignest

Equally, of both the peer,

All things fillest, all things lovest,

Planets guidest, heaven movest,

Yet unmoved dost persevere.”

They, no less than the men of the eighteenth century, were impressed by the movements of the celestial

bodies, but to them it was something alive, not something mechanical. Well, I suppose they were naïf

about their science, just as the men of a later age were naïf about their philosophy. But I always feel that

we have lost something, we modern Catholics, something of that splendid boldness with which the

medieval treated all experience as one. We think of the Holy Spirit, don’t we, as concerned with us men,

as helping us in our decisions, as quickening us with more fervor of devotion; we do not feel the draught

of his impetuous movement in the world around us. We are all so scientific.

Well, be that as it may, we have got to believe, on pain of heresy, that the Holy Spirit does interfere, all

the time, in your life and mine; that his influence plays over us, like the steady breeze which fills the sails

of a boat, or like the sudden gusts which send the autumn leaves spinning in the air. At least, I don’t know

that that is really a very good comparison. Because the wind catches the surface of things; when it is

blustering on the hill-tops you may be sheltered from it in the valley. Whereas it is a plain fact of

experience that the operations of the Holy Spirit do not manifest themselves on the surface; they take

effect within. They belong to that hidden self of which we have been speaking, the self that lies below the

level of consciousness. Below? Perhaps above; but at least beyond the range of our knowing. When you

stand in the face of some important decision, when (for example) you are electing your state of life, you

naturally invoke the aid of the Holy Spirit. But, having done that, you proceed to make up your mind

exactly as you would have made it up in any case; by weighing arguments, by taking human advice, and

so on. You do not expect a sudden illumination from heaven to break in upon your calculations. Even on

those rare occasions when a salutary thought strikes you quite out of the blue, with no previous train of

thought to account for it, you say, perhaps, “It was an inspiration”; but then you reflect, “How can I be

certain of that? How do I know what hidden association of past memories may have set my brain working

in that way? Perhaps it wasn’t an inspiration after all.” But it was; there’s nothing to prevent the Holy

Spirit using some association of past memories in your brain cells to produce the effect he wanted. The

breath of God stirred over the turbid waters of your unconscious self, and said, “Let there be light.”

What I’m trying to suggest is that most of us have a rather limited view about the help we expect to

receive from the Holy Spirit. Our devotion to him is real, but it is something that we keep for special

occasions; moments of vital decision, or acute spiritual crisis. It is so easy to think of yourself as a boat

propelled by machinery, which can get along all right most of the time by its own power – it’s only when

the engine breaks down that you bother to hoist the sails. When I used to teach at Old Hall you would get

summoned, now and again, to some meeting of professors to discuss College business; and you put your

pipe in your pocket on the chance; but if the meeting began with Veni Creator Spiritus you knew that you

might just as well have left it behind. I don’t want to criticize my old college, but it did and does seem to

me that there’s a slight tinge of Jansenism about the idea that if you light a pipe the Holy Spirit ceases to

take any further interest in your deliberations. We forget, you see, how constant and how intimate is the

play of his influence on our lives. But why should we? We’ve lost, no doubt, the medieval trick of tracing

it in the movements of the heavens, but surely we ought to trace it in the mysterious movements of our

own minds, stirring over that primeval chaos which underlies the cosmos of our daily thoughts?

It isn’t true, and of course it can’t be true, that only the impressions of early childhood have the power to

mould a man’s character. On the contrary, we are building it up all the time; from hour to hour the

complicated tapestry of our lives is being woven out of fresh material. We are accustomed to remember

that, when it is a question of the will making some conscious decision – consenting, for example, to sin.

Every sin, the spiritual authors hasten to assure us, diminishes in some tiny degree our capacity to resist

the next temptation. But, you see, it isn’t only our moral choices or even our conscious thoughts that have

this power to affect us; all the time we are taking in something from our surroundings. Just as our bodies

are exposed, day by day, to a hundred dangers which we cannot see, so our minds can be influenced by

things which don’t seem to matter; sights and sounds that were hardly registered, impressions which at

the time had no moral significance, no taint of sin and no relish of salvation in them, can leave their mark

ever so slightly, and help to make us, for better or worse, the people we are.

I’m not saying this to frighten anybody or make anybody scrupulous; I’m only trying to point out that

when you and I invoke the Holy Spirit we are not just inviting him to be there in case of accidents. We are

recognizing that there is a whole world of minute mental happenings which, but for his watchful care,

may turn to poison for us. We are asking him to guide us, not only in the momentous choices which seem

to us important, but in every tiny decision of our wills, because the effects, even of such a decision, may

have results beyond our knowing. One has heard of sectaries who would not even cross the street without

asking for guidance; we may laugh at their scruples, but we have to admit that they are distortions of a

true principle.

Don’t let us be content, then, to ask the aid of the Holy Spirit in getting the better of our temptations; let

us ask him also to do something about this background of sinfulness from which our temptations arise,

this chaos of hidden, conflicting tendencies within us which is, which has become, our nature. There is a

work of cleansing and of mending to be done in us at a level which escapes our observation altogether.

That haunting list in the fourth verse of Veni, Sancte Spiritus is not a list of sins; it is a list, drawn up

under various images, of those faults in our nature which are the context of our sinning.

Lava quod est sordidum, wash clean what is sordid. What is filthy, if you will; but in our speech that

metaphor has a narrow compass; defilement conjures up in our minds the picture of sensual temptations.

It is natural that it should be so; dirt is only displaced matter, and those sins in which sex plays a part are

only the abuse of a noble thing in our nature. But in the language of the New Testament the word

“defiled” has a more general meaning; when St. James, for example, tells us to cast aside all defilement,

and all the ill-will that remains in us, he seems to be thinking of that mean streak in our natures which

rejoices in taking unfair advantage of an enemy. What is sordid in us is what we ourselves would be

ashamed of if it came to light. When you are moved by jealousy to detract from the praises of some rival,

that is sordid. When you grudge somebody the help he might expect of you, just because he is a bore and

uncongenial to you, that is sordid. Not only from the rebellion of sensual desires, which makes itself

clearly felt, but from the meanness which hides itself away under so many cunning disguises, we ask to be

delivered when we pray Lava quod est sordidum.

Riga quod est aridum, water the parched soil. When we say that, we are not thinking only of disabilities

which arise from our own fault. There is, as we all know, a dryness in prayer which belongs to a different

category. Commonly – I think you can say, most commonly – it is not the result of sin or a punishment of

sin, but a discipline which God sends us by way of testing the quality of our love for him. And if we ask

the Holy Spirit to lighten that discipline for us, it is only from a salutary fear that we shall not be able to

stand the test. But there is a dryness in our human contacts which is a defect in us, and often a defect

which grows in us. A kind of selfishness cuts us off from our fellow-men; we can’t summon up the effort

to make friends of people. From this ingrowing selfishness, our fault only in part, we ask that we may be

delivered.

Sana quod est saucium, cure what is wounded in us. There we find ourselves talking the language of

psychology. Our traumas; the irrational antipathies, the unaccountable phobias which seem to mark us out

from our fellow men – they have become part of our nature, and we can do nothing about them. We can

do nothing about them, and therefore we ask the Holy Spirit to heal us, if he will, of these forgotten

wounds which so hamper our activity.

Flecte quod est rigidum, bend what is stiff in us. That difficulty of approach which our neighbors find in

us, so largely due to mere shyness, mere awkwardness; that unsympathetic attitude towards the failings

which we don’t evidently share; that self-withdrawal which isn’t quite pride but is next-door-neighbor to

it – we want to be rid of that too.

Fove quod est frigidum – chafe what is numb. Sometimes a kind of torpor creeps over the mind, like the

chill of old age, deadening (or so it seems) the faculties of the spirit; our zeal for souls, our hope of

salvation, even faith itself, haven’t been lost, but it’s as if they had been sealed off, like a finger or a foot

rendered insensible by frost. What is the explanation of it, where lies the fault in it, and how grave, we

cannot tell; but oh, if it could be chafed back to life!

Rege quod est devium – straighten out what is warped. What a curious thing it is, the cross-grainedness,

the contrariness of some people; how a man can so want to be different from his fellows that he differs for

the sake of differing; enjoys the martyrdom of intellectual loneliness; delights in shocking the prejudices

of his neighbors. Oh, it is harmless enough on a small scale, and often amusing; but it is a dangerous kink,

not always far removed from pride. If the Holy Spirit would iron out those exaggerated eccentricities,

bring us back again to the true!

“The Spirit,” says St. Paul, “comes to the aid of our weakness; when we do not know what prayer to offer,

to pray as we ought, the Spirit himself intercedes for us, with groans beyond all utterance.” Down in the

depths of our fallen nature he is at work, reinterpreting us to ourselves, subtly fashioning us, according the

measure of the perfect man in Christ – without our knowledge, but not, perhaps, without our asking for it.

Ronald Knox

Excerpted from ‘The Layman and His Conscience’